Powerful Place. St. Magdalena im Halltal

This very special place in the Halltal valley - in the middle of the Karwendel Nature Park - was not chosen as one of our places of power for nothing. To reach this Powerful Place, you first have to venture into a rugged, impressive valley. The path into Halltal reveals many a boundary. This makes it all the more beautiful to reach your destination after around two hours: The Chapel of St. Magdalena, a former monastery was built in a wonderful spot, a wide clearing in the forest.

Even in earlier times, people knew about the special effect of some places. It doesn't hurt that there is a traditional mountain inn right next to the chapel. So mind, soul and body are well catered for.

The former toll road has been closed to motor vehicles since 2012 - today, hikers and chamois enjoy a car-free Halltal valley. For those who cannot or do not want to take a shortcut by car, there is a cab service.

The power place St. Magdalena at a glance

- Experience salt history on the brine hiking trail

- St. Magdalena excursion inn with small church

- Austria's largest protected area: the Karwendel Nature Park

- Shuttle service to St. Magdalena on the summer weekends

- Wild and romantic valley with impressive flora and fauna

The story of St. Magdalena

History of the origins of St. Magdalena in Halltal

The first monastery and a chapel in honor of St. Rupert were founded in 1441. However, the "Forest Brothers", as this monastic association was called, only remained in Halltal until 1447. In 1448, two Forest Sisters, who lived according to the rules of the Augustinian order, moved into the monastery in Halltal. And so, despite the harsh climate, the convent flourished at the end of the 15th century. In the early eighties of the 15th century, work began on a new building. In 1494, the convent was home to 24 nuns and a chaplain. In 1495, the future Emperor Maximilian I issued the convent with a special letter of protection.

Convent complex with church and farm buildings

The outside of the church has no divisions and no tower. The choir and nave are the same width. Inside, the vault has star ribs with round keystones on octagonal wall consoles. The vault painting in the choir shows the year 1486, which is probably the year the building work was completed. The reason why the place is called St. Magdalene is probably because in 1490 the church consecration day was moved to the day of Mary Magdalene by the Prince-Bishop of Brixen. The reason for moving the church consecration day could be that Magdalena, the daughter of a wealthy Hall citizen (Georg Perl), had entered the convent in 1486. Georg Perl donated 20 Mark Berner annually so that his widowed daughter could live in the convent together with his granddaughter, also Magdalena. Another reason is probably that St. Magdalene (along with St. Rupert, St. Nicholas and St. Barbara) is one of the most important mountain saints.

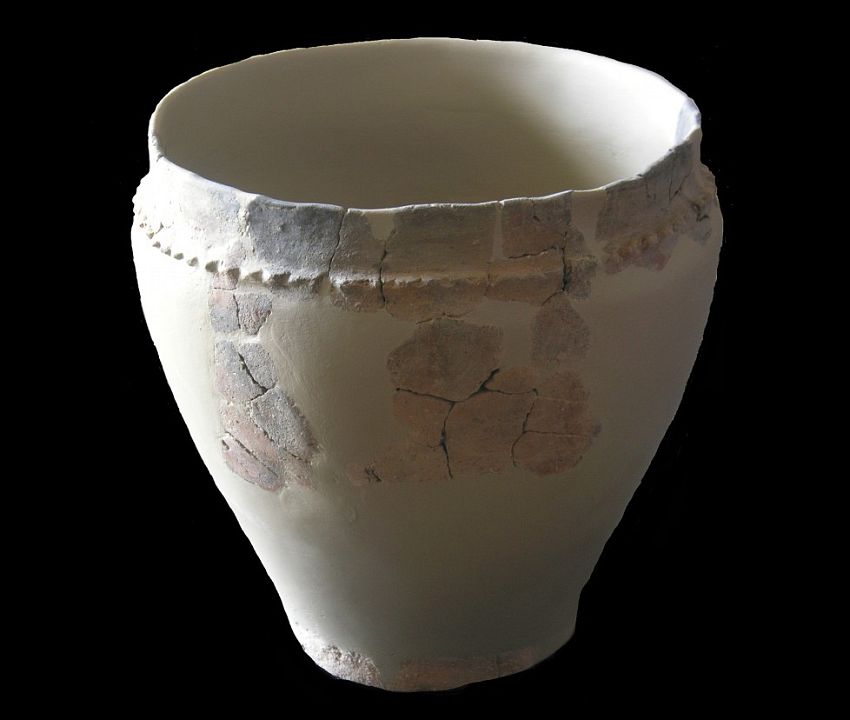

The nuns gradually moved away from the convent (some of them to St. Martin in Gnadenwald) and so in 1566, the convent was completely dissolved. The convent quickly fell into disrepair, with only the church being preserved by the Hall salt works. The former monastery building now houses an excursion inn. The old brick cellar of the monastery, which served as a refuge from avalanches and a place to store food, still exists. The church is still in good condition today. It was restored in 1946, 500 years after its first consecration. Every year, the patron saint's day is celebrated on the Sunday closest to St. Magdalene's Day (July 22).

The former monastery complex of St. Magdalena also included the farm building to the south of the church. In 2004/2005, the building (mixed construction with a gabled roof) was saved from decay through a general renovation. The wooden structure of the threshing floor and the barrel-vaulted stable room are now used for events.

The winged altar in the cemetery chapel in Hall

The late Gothic winged altar from the 2nd half of the 15th century was originally located in the monastery church of St. Magdalena in Halltal and was moved to Hall's Magdalen Chapel in 1923. It was probably made by the Innsbruck workshop of the painter Ludwig Konraiter. In the shrine, St. Margaret (left) and St. Catherine (right) flank the central Madonna figure. The side wings depict a Marian cycle (Annunciation, Visitation, Adoration of the Child by the Magi and the Death of Mary). The predella shrine depicts the Nativity, the predella wings St. Barbara and St. Agnes. Margarethe, Katharina and Barbara are popularly known as the three "Holy Tyrolean maidens". According to their attributes, they are accompanied by the following proverb: Barbara with the tower, Margarethe with the worm, Katharina with the wheel, these are the three holy girls.

Salt mining around Sankt Magdalena in the Halltal valley

The foundation of St. Magdalena is closely linked to salt mining.

Several legends go back to the discovery of salt deposits in the Halltal valley in the 13th century. One of them tells us that in the 13th century (1275), Knight Nikolaus von Rohrbach was out and about in the Halltal valley and struck up a conversation with his hunters. They told him that they had observed red deer licking eagerly at a stone. As the deer were thriving so wonderfully - almost as if they were getting salt stones - there must be something special about this rock. Nikolaus von Rohrbach checked it out and discovered that the stone did indeed taste salty. This was the birth of salt mining in Hall, so to speak. The first tunnel was opened in 1272. At first, the salt was boiled directly at the top of the mountain, only later was the brine transported to the valley by means of brine pipes (hollowed-out tree trunks, from 1903 cast iron pipes) and boiled there in the brewhouses at the salt works.

The hike up to Sankt Magdalena tells this impressive salt story. A few steps after the start of the asphalt road, you will see the Berger Chapel on the right. Miners and miners were called "Berger" in the vernacular. Inside the chapel we find three paintings from the late 17th century. The miners' freyung began at the Berger Chapel. This meant that neither the Thaur magistrate nor the town magistrate of Hall were allowed to arrest a miner within this enclosure. Even if he was accused of a serious crime. The right to arrest was only reserved for the Salzmair (management of the salt works and mining). Although this freedom has existed since the 14th century, it was only recorded in writing by Emperor Maximilian I in 1502.

Ladhütten, escape route and manor houses

We discover a total of three loading huts on the way through the Halltal valley. They were used by miners as stops for wagons, shelters and resting places.

Shortly after the mountain chapel, the escape route branches off to the left. It was used by the miners to get safely to their workplaces or back to the valley in the event of an avalanche. Avalanches and mudslides have always posed a major threat to this area and still often block access to Sankt Magdalena today. The miners could often only hope for divine assistance. Numerous masses were said and petitions were made.

The so-called manor houses are an outstanding testimony to the former mining industry in Halltal. They are located at the head of the valley and were the center of 700 years of salt mining in Hall. The manor houses in their present form were built between 1777 and 1791. They served as the former administrative buildings of the salt mine and provided accommodation for the miners. Unfortunately, an avalanche destroyed large parts of the manor houses in 2001.

The tunnels in the Halltal valley

Over the centuries, a total of eight tunnels were built on several levels. The Kronprinz-Ferdinand Stollen (1334 m) or Glück-Auf-Stollen was excavated in 1808 and is the youngest. The Erzherzogsbergstollen (1422 m) goes back to Archduke Ferdinand Karl (died 1662). The Kaiserbergstollen (1485 m) is located below the manor houses. It was opened by Emperor Ferdinand I in 1563. The König-Max-Stollen (1485 m) was located in the center of the mining sites above the Herrenhäuser and was opened in 1492 by Emperor Maximilian (then still king, hence the name!). It has been possible to take a look inside this gallery again for some time now. The Steinbergstollen (1533 m), just above the Herrenhäuser, was probably opened around 1400. The mine smithy stood next to the tunnel hut and a residential building to the west of it. The Mitterbergstollen (1574 m) was opened by King Henry of Bohemia, Count of Tyrol and Gorizia around 1314. A spacious residential building (for around 90 miners) was built next to this tunnel. However, it was badly destroyed by an avalanche in 1951. The oldest is the Oberbergstollen (1608 m) and was excavated in 1270, presumably at the same time as the Wasserbergstollen (1635 m). The latter was only used indirectly for salt production, as it was used to water the salt pits in the deeper tunnels. Because it was very safe there, a residential building and stables for the carters were built nearby.